I’ve always liked building emulators. They’re quirky, and with a reasonable amount of time you can actually build something that does something. I had this NES emulator project sitting half-implemented for a few years, collecting digital dust. Recently, I figured it wouldn’t require that much love to get it minimally working, so I picked it back up.

Building an NES emulator starts with the CPU - the 6502. The instruction set is well-documented, and implementing the basic opcodes is relatively straightforward. There are many official opcodes, plus a bunch of unofficial ones that various games rely on. It was somewhat tedious, but once the scaffolding for the CPU and opcodes are laid down, you can get most of them banged out just from reading the reference documentation.

Getting things like cycle counts (different depending on addressing modes) and setting flags correct is pretty tricky, and I wasn’t going to get it correct on first implementation. That leaves the question: how do you actually

know if you’ve implemented something correctly? Interestingly (and thankfully), there are a ton of homebrew ROMs that are built just to test emulators. I used one called nestest.rom that tested all the opcodes and other

behaviors against a giant log to compare against (making this ROM useful even before you have the graphics systems implemented). There are still some fixes I had to make that I don’t quite understand because they seem to

contradict the documentation, but I had the tests passing.

This is where things got more frustrating. The NES isn’t just a CPU - it’s a complex system with a PPU (Picture Processing Unit), APU (Audio Processing Unit), memory mappers, and all sorts of timing-sensitive interactions between components. I will spare you the details, but if you write this emulator yourself, be prepared to spend a bunch of time trying to figure out why games are hitting infinite loops because interrupts aren’t working how they should. It’s relatively easy to build debugging tools and tests around these things though, so you just have to really dive into the investigation fully, and usually the fix ends up being simple. It’s also tricky because games seem to do things they aren’t supposed to (writing to read only carterage memory???), so it can be difficult to decide whether the game is doing something silly or whether your emulator did something silly 1000 instructions ago.

This project included my first experience using generative LLMs for coding. I was never hugely invested into this project when I picked it back up, so I didn’t really want to dive into the extremely complicated world of rendering for the NES, supporting all the different rendering modes and features. I figured I’d give an LLM (GPT-5) a crack at building something minimal so I could actually see a game run.

The results were… mixed. The first iteration of the renderer worked well (seemingly), and I booted up a game and was presented with an image. But there were things missing or not rendered right – features missing and bugs from the initial implementation. Prompting the LLM to increase feature coverage and fix issues didn’t go very far, I’m guessing because there’s too much highly detailed knowledge of the NES’s PPU and graphics implementation, and fixes can’t be made just by looking at the existing code. The LLM also struggled keeping track of the design of the system. When implementing a new graphics feature that I would have judged to require architectural changes or new abstractions, it would just keep applying local hacky patches. It couldn’t see the quality of the software descending over time.

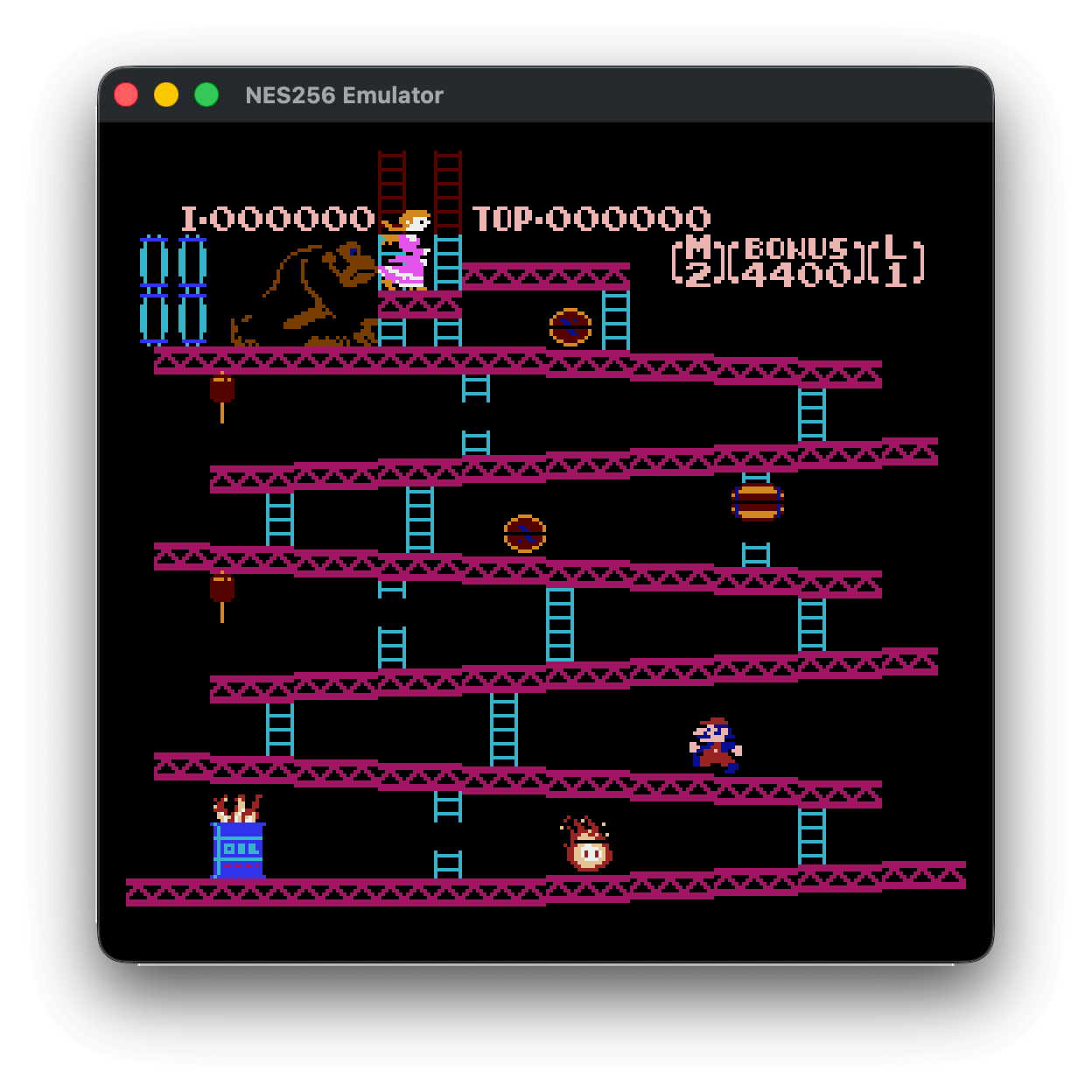

Overall, I got what I wanted – a couple games that rendered correctly. But the LLM couldn’t take me past a basic implementation, and I feel uncomfortable knowing that I have zero knowledge of where the land mines are in this implementation.

The emulator can run some games like Donkey Kong and Super Mario Bros., but there are still compatibility issues with more complex titles. The audio isn’t implemented yet, and the extended feature set of the NES is largely unimplemented (different cartridge formats, banked memory, different controller types, etc.). This is probably where this project ends.