I’ve toyed around with building small kernels before, but never getting far enough to actually run a userspace. For whatever reason, I was in the mood to find an excuse to write some C code, and this felt a perfect opportunity (as it turns out, I would not get to write much C code).

To be clear, I wanted to build a userspace from scratch – no glibc, no systemd, no unix

userland executables like ls or chown, etc. I’ll have to build my own versions of

these things.

The first step was to build a linux kernel. My userspace targets x86_64 but my host machine is an arm macbook, so we’re going to have to cross-compile the kernel. With the right tools, this turns out to be pretty easy.

The next step is to build a bootable image. This turned out to be a big leap knowledge-wise because I had no idea how to stitch together a kernel and userspace. At this point, I didn’t even have a userspace, so I had to build a minimal one.

I started with BusyBox, which is a single binary that contains many common unix userland

commands. This is convenient for us because it means we can statically link this binary with

an x86_64 libc installed on our host machine, and it should just work. We’ll also need an

init script that the kernel will run on boot, and a thing called an initramfs which

is a filesystem that the kernel will mount as the root filesystem. The initramfs will contain

our BusyBox binary and the init script (which at this stage is just a shell script that

runs the BusyBox sh to give us a shell).

After a lot of reading, this starts to make sense and I’m able to finally assemble a bootable image containing our kernel and initramfs. I can boot this image in QEMU and get a shell!

Now that we’ve actually got an OS booting, it’s time to start swapping out BusyBox for our

own userspace. This turns out to be another big leap knowledge-wise. I’ve only vaguely heard

of this thing called a crt0, I only have a basic understanding of the linux syscalls (and no

knowledge of x86_64 calling conventions), there’s major blind spots in my understanding of

the libc API and implementation, and I’ve got no clue how to link everything together.

The first step turns out to be building a crt0 which is some code that is linked into

userspace binaries that sets up the environment for the program to run. The crt0 is responsible

for setting up the stack, setting up the environment and argument pointers, calling main function,

and cleaning up after the program exits. There are some good references online and it’s easy-ish

to cobble together a basic crt0 asm file.

The next step is to build an init binary that will be run by the kernel on boot. If we can figure

out how to link this binary with our crt0, then we can start with a infinite loop and skip

even needing a libc. Somewhere around here I get annoyed dealing with plain Makefiles and

fight my way through setting up a CMake build system that can build the kernel,

compile and link our userspace binaries, build the initramfs, and create the bootable image.

Now, we’ve got an infinite loop after booting! (Probably – after all, nothing is actually happening

in the console).

If we want to do anything useful (like print to the screen), we need a C library. First up

we’ll need to implement the libc write function. On a linux system, this is just a wrapper

around the write syscall, so we’ll need to implement syscall support in our userspace.

Thankfully, we can reference the linux kernel source code to see the syscall numbers,

and thanks to the power of multi-cursor editing, we’ve soon got another assembly file

that contains our syscall implementations (with invalid x86_64 calling conventions as it

turns out, but thankfully I’ll notice and fix this before it bites me).

I create our unistd.h header, define the write function, and give it a basic implementation

that just passes the arguments to our syscall implementation. Now if we statically link our init binary

against our libc, we can call write with file descriptor 1 (stdout) and print to the screen!

Now that we’ve got our scaffolding in place, we can start implementing more unix userland binaries

and libc functions (oh, and libm functions also). I start with some basic binaries like cat, ls,

and importantly, a totally non-POSIX-compliant sh shell that can run simple commands.

We’re starting to run into trickier things to implement: malloc, printf, and functions that

use FILE and DIR structs. Actually, malloc turns out to be pretty easy to implement if

you use a simple bump allocator and never free memory. printf is a bit more tricky, but

I can just implement a basic version that only supports %s and %d format specifiers. Functions

that use FILE and DIR structs are a bit more involved, but I can implement a basic version

that only supports reading and writing files, and listing directories (and in the process finally

learn how these structs work and what they contain, since the contents are implementation-defined

for the most part).

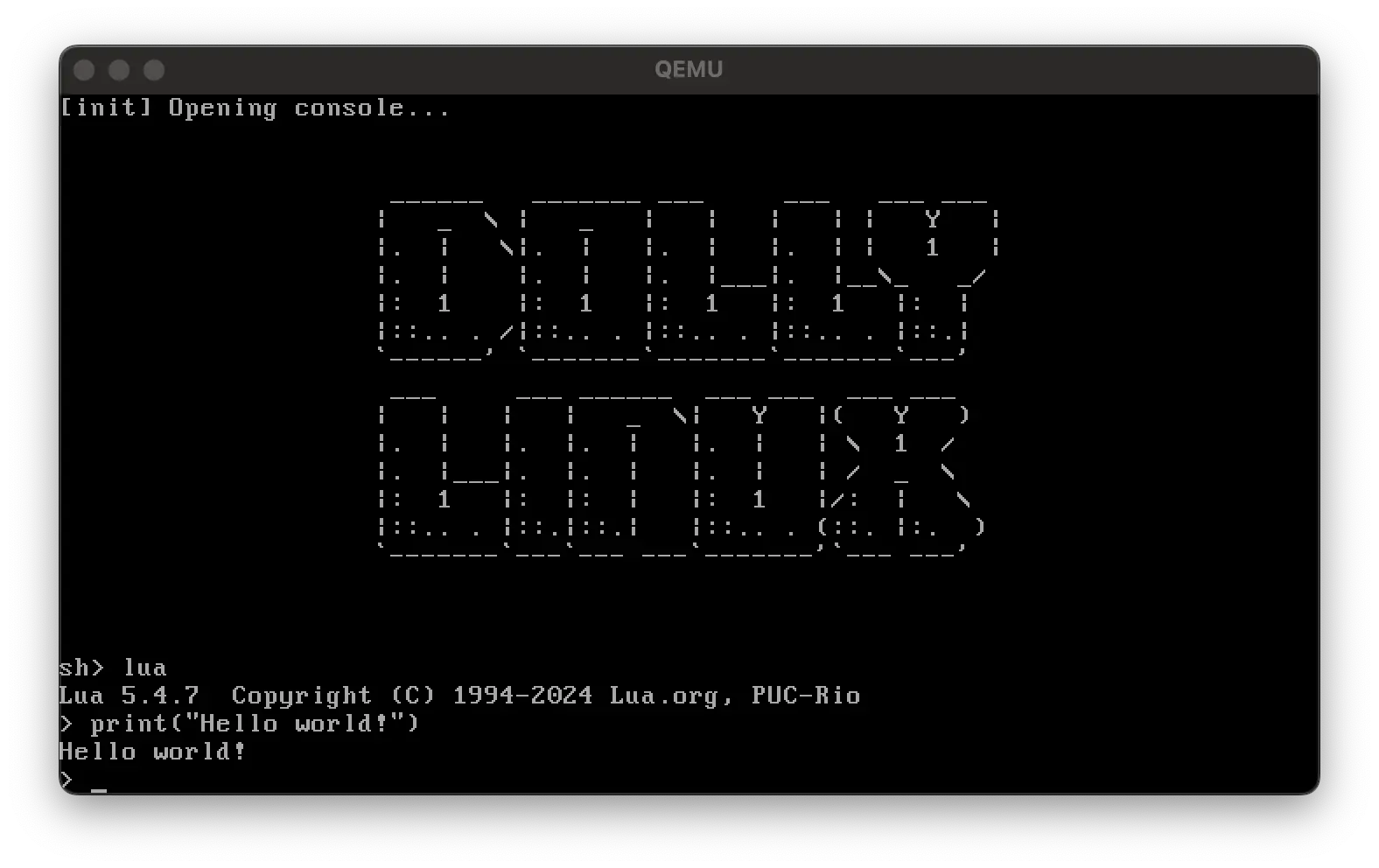

We’ve got some basic utilities and a tiny amount of libc implemented, but our OS doesn’t really do much yet. So, let’s try to run Lua on it! Lua is a good choice for this because it has a small footprint, no dependencies, can be statically linked, is extremely portable, and has broad coverage of C stdlib functions.

Trying to build Lua against our libc immediately blows up into a thousand errors. We are missing a lot of C stdlib functions. It takes me a few hours to define all these functions in the right headers, and it magically compiles! But… it won’t link – I didn’t actually implement these functions yet, so we’ve got a bunch of undefined references. Thankfully, most of these are more syscall wrappers and nothing too tricky pops up.

I run the Lua repl for the first time and it crashes. I’ve got some bugs in the libc implementation and it’s tough to track them down, but eventually we get it working. I can now run (some) Lua scripts on my userspace!

There’s a lot more to do here. I want to implement a proper malloc that can free memory,

implement more libc functions, and build more userland binaries. I also want to

implement a proper shell that can run commands, a terminal emulator that can improve the

serial-console experience, and possibly take this into the modern era with a graphical

environment by implementing a framebuffer driver and X11 implementation.